Table of Content

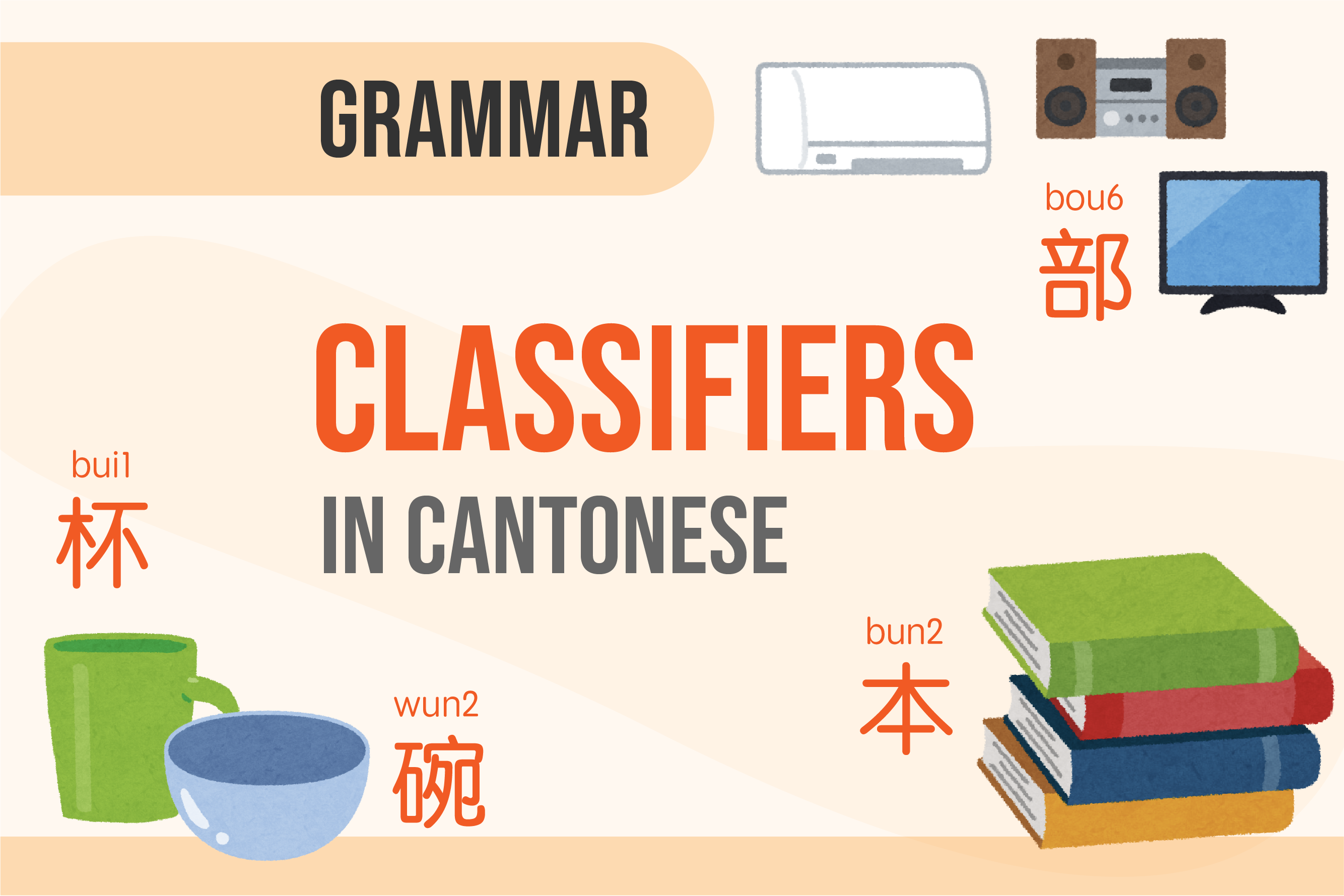

Classifiers, sometimes referred to as measure words (量詞), are an important but often complex topic in Cantonese. There are some words in English that function similarly to classifiers, typically used when measuring uncountable nouns, for example, "a drop of water," "two cups of coffee," "a piece of paper," or when grouping plural countable nouns, such as "a flock of birds" or "a box of apples."

At this point, you might think, 'Okay, it seems pretty straightforward.' But not all Cantonese classifiers have direct English equivalents. This is because English usually doesn’t use measure words for countable nouns, especially for singular ones (since they’re already countable, it seems like there’s no need for an extra measure word). However, in Cantonese, almost every object needs to be used with a classifier, and there isn’t always a clear rule for which one to use.

Before we dive into how to use classifiers and which ones to choose, let’s first understand when classifiers are needed. As the name "measure words" suggests, they help in measuring or counting objects, but they are also required in other contexts.

When Do We Use Classifiers?

Unlike in English, where measure words are optional before nouns, in Cantonese, classifiers are almost always required when 1) a determiner or 2) a demonstrative pronoun is used. If these terms seem confusing, here are some examples:

本 is a classifier for book-like objects which cannot be directly translated into English.

Numeral determiners: 一本書 (one book), 兩本書 (two books)

Demonstrative determiners: 呢本書 (this book), 嗰本書 (that book)

Definite determiners: 本書 (the book)

+Possessive determiners: 我本書 (my book), 你本書 (your book)

*Quantifier determiners: 幾本書 (a few books)

#Distributives determiners: 每本書/本本書 (every book)

Demonstrative pronouns: 呢本(係字典) (This is a dictionary)

For those who enjoy definitions, a determiner is a modifying word that determines the kind of reference a noun or noun group has, while a demonstrative pronoun points to and replaces specific people or things.

How Do We Use Classifiers?

For determiners that are always followed by a noun, such as "one book" or "this book," classifiers are used between the determiner and the noun (or simply before the noun for definite determiner):

【(Deteminers) - Classifier - Noun】

一本書

One book呢本書

This book我本書

My book本書

The book

For demonstrative pronouns, which replace the noun itself, such as "This (is a dictionary)" or "That (is a wooden table)," the classifier follows the demonstrative:

【Demonstrative - Classifier】

呢本係字典

This is a dictionary.嗰張係木枱

That is a wooden table.

Which Classifiers Should We Use?

Now for the most important part: how do you determine which classifier to use? To start, it's important to understand that there are two main types of classifiers: sortal and mensural, each differing slightly in their nature and usage. Some classifiers, however, can function as both sortal and mensural, depending on the context and the nature of the noun they are paired with.

Mensural Classifiers

Mensural classifiers are generally more understandable to English speakers, as they can often be directly translated into English and applied to different nouns as long as it makes logical sense. They are similar to most of the measure words in English, such as cup, bowl, bag, bottle, etc., which quantify nouns based on measurements, quantities, or portions. They often express units of weight, volume, length, or other measurable aspects.

These are typically used for uncountable nouns (as in examples 1-4) or plural countable nouns (as in example 5) and usually serve as a unit of measure.

一滴水

one drop of water兩杯咖啡

two cups of coffee

(兩 is used instead of 二 when followed by a classifier)三羮糖

three spoons of sugar四碗飯

four bowls of rice五箱蘋果

five boxes of apples

Sortal Classifiers

Sortal classifiers, on the other hand, are unique to Cantonese (and many other Asian languages), and most of them cannot be directly translated into English. These classifiers are inherently tied to the nouns they accompany, often based on the nature, characteristics, shape, size, or attributes of the object unless the objects can take various forms.

They are generally used for singular and plural countable nouns, where English typically doesn't use measure words (as in examples 1-4), or sometimes for uncountable nouns where measure words are used in English (as in example 5).

六本書

six books(本 - for book-like reading materials, such as a books, magazines, comics, dictionaries, etc.)

七枝筆

seven pens(枝 - for long, straight, hard objects, such as pens, sticks, toothpicks, etc.)

八隻狗

eight dogs(隻 - for animated objects or eating utensils, such as animals, bowls, plates, etc.)

九部電話

nine phones(部 - for devices or machines, such as phones, computers, cars, etc.)

十張紙

ten sheets/pieces of paper(張 - for flat objects or furnitures with flat surfaces, such as papers, tables, chairs, etc.)

張 is a sortal rather than a mensural classifier. This means 張 is inherently tied to the noun 'paper' because of its characteristics—being broad, flat and thin.

In English, 'sheet' or 'piece' function like classifiers for the uncountable noun - 'paper'.

The main difference between these two types of classifiers is whether the classifier is semantically connected and inherently tied to the object, based on its nature.

Sortal | Mensural | |

|---|---|---|

Singular Countable Nouns | Yes | No |

Plural Countable Nouns | Yes | Yes |

Uncountable Nouns | Yes (less) | Yes (more) |

Can be directly translated into English | Mostly no | Mostly yes |

Flexibility with nouns | Typically tied to specific nouns | More flexible as long as it makes logical sense |

Generic Classifiers

Cantonese has two generic classifiers:

個: A sortal classifier used for many objects without a specific classifier, similar to a "miscellaneous" category.

啲: A classifier for plural nouns and uncountable nouns, indicating a small amount or number greater than one, without specifying the exact amount.

You can use 個 in almost all cases, but 啲 cannot be used with numerals greater than one or with quantifiers and distributive determiners. For example, with 橙 (oranges):

個 | 啲 | |

|---|---|---|

Numeral determiners | ✔ 一個橙 ✔ 兩個橙 | ✔ 一啲橙 ✘ 兩啲橙 |

Demonstratives determiners | ✔ 呢個橙 | ✔ 呢啲橙 |

Definite determiners | ✔ 個橙 | ✔ 啲橙 |

Possessive determiners | ✔ 我個橙 | ✔ 我啲橙 |

Quantifier determiners | ✔ 幾個橙 | ✘ 幾啲橙 |

Distributives determiners | ✔ 每個橙/個個橙 | ✘ 每啲橙 |

Demonstrative pronouns | ✔ 呢個(係橙) | ✔ 呢啲(係橙) |

Flexibility with nouns | A lot but not all | Almost all |

Although 啲 is more restricted in terms of the types of determiners it can be used with, it is actually applicable to almost all nouns.

On the other hand, while 個 can be used with all determiners and demonstrative pronouns, it is restricted to a list of specific nouns – though that list is fairly extensive.

Tips for Deciding Which Classifier to Use

When deciding which classifier to use, a good rule of thumb is that if there’s already a measure word in English, you can usually translate that word directly into Cantonese. In most cases, these objects are uncountable nouns.

For uncountable nouns that are without measure words in English or

For countable nouns, where usually there isn't any measure word in English, if they are plural and you are using the determiners listed below or demonstrative pronouns, most of the time you can use 啲:

Demonstrative determiners: 呢啲書 (these books), 嗰啲書 (those books)

Definite determiners: 啲書 (the books)

Possessive determiners: 我啲書 (my books), 你啲書 (your books)

Demonstrative pronouns: 呢啲(係字典) (These are dictionaries)

For singular nouns, or if you need to specify the amount of plural nouns (when counting) or quantifier/distributive determiners (a few/every), you’ll have to use the correct classifier (usually a sortal one). See examples in the "When do we use Classifier?" section above.

If you’re unsure, the last resort is to try using the generic classifier 個—it’s better to use a classifier in Cantonese than not to use one at all, and many objects pair with 個, so you might actually get it right!

Extra Notes

For objects that can have various forms, there may be more than one sortal classifier for a single noun. For example, a bread can be 一個/一嚿麵包 (個 is a generic classifier | 嚿 is used for object without a definite or regular shape), while a loaf of bread is 一條麵包 (條 is used for long, soft, curved objects).

You should also note that you can't always directly translate classifiers from English to Cantonese. For example, you can't directly translate the classifier "piece" as 張 in all cases as a piece of cake is 一件蛋糕 and a piece of pizza is 一塊薄餅.

Also remember that classifiers in Cantonese and Mandarin are not exactly the same, so if you understand Mandarin, you might find that the appropriate classifier for a noun in Cantonese differs from those in Mandarin.

Footnote

+The usage of possessive determiners with classifiers only exists in Cantonese but not Mandarin. In mandarin, 的 is used as “'s” in English for all nouns to indicate possession.

*Not every quantifier determiners in English are used with classifier in Cantonese, for example, many books can be 好多書 or 好多本書, but few books can only be 少少書 but not 少少本書

#Not every distributive determiners in English are used with classifier in Cantonese, for example, all books is 全部書 but not 全部本書